Quickstart

The timetool is used to correct for inherent jitter in the arrival time between an optical laser pump and x-ray probe. In most cases, if the timetool has been set up properly, it is possible to simply use the DAQ's default analysis to extract this difference in arrival time. You will still need to calibrate the timetool: read the section on calibration to understand why and how. Then you can blindly use the results provided by LCLS. Lucky you! The information here on how the timetool works may still be of interest, and if you have decided to just trust the DAQ, you have a lot of free time on your hands now – so why not learn about it?

In many cases, however, re-processing of the timetool is desirable. Maybe the tool was not set up quite right, and you suspect errors in the default analysis. Or you are using 3rd party software that needs to process the raw signal for some reason. Or you are a hater of black boxes and need to do all analysis yourself. If you wish to re-process the timetool signal, this page explains how the 'tool works, and presents the use of psana-python code that can assist you in this endeavor. That code can probably do what you want, and can act as a template if it does not.

Enough rambling. To femtoseconds!... ok ok but not beyond.

Principle of Operation

Before embarking on timetool analysis, it is useful to understand how the thing works. Duh. The TT signal comes in the form of a 2D camera image, one for each event (x-ray pulse). The tool measures the time difference between laser and FEL by one of two methods:

- spatial encoding (also called "reflection" mode), where the X-rays change the reflectivity of a material and a laser probes that change by the incident angle of its wavefront; or

- spectral encoding (also called "transmission" mode), where the X-rays change the transmission of a material and a chirped laser probes it by a change in the spectral components of the transmitted laser.

Nearly all experiments use option #2. If you are running in option #1, ignore the rest of this page and get help. I will proceed describing mode 2.

A "timetool" is composed of the following elements:

- A laser setup that creates a chirped white light ~ps length pulse concurrently with the pump

- A "target", usually YAG or SiNx, that gets put in the path of both the white light and LCLS x-ray beam

- A diffraction grating that disperses the white light pulse after it goes through the target

- A camera that captures the dispersed white light

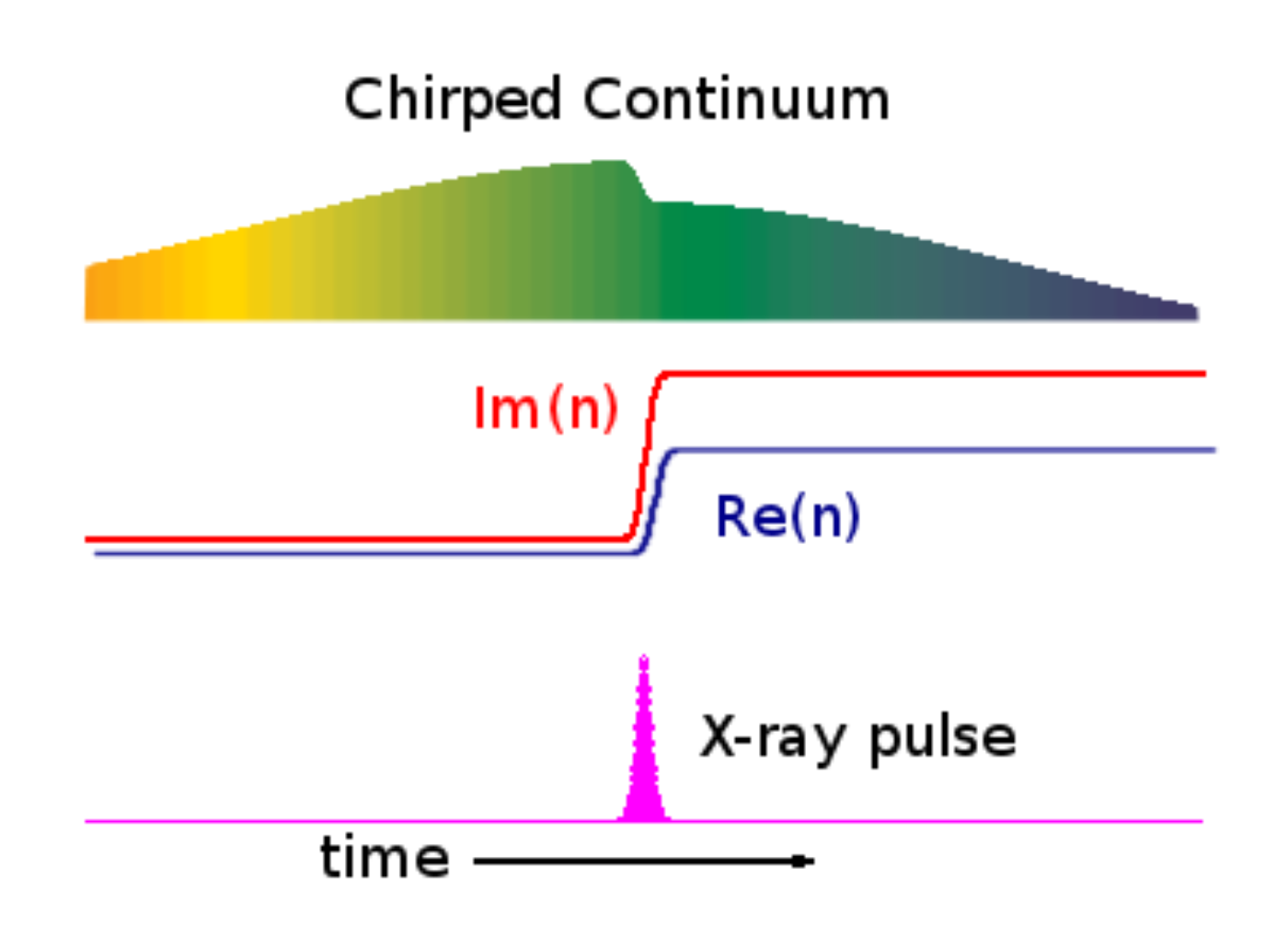

The white light propagates through the target, with shorter (bluer) wavelengths arriving first, and longer (redder) wavelengths arriving later. Somewhere in the middle of passing through the target, the x-rays join the party. This causes the index of refraction of the material to change, and generates an edge in the white light power profile (in time, and therefore also spectrally, due to the chirp). See figure:

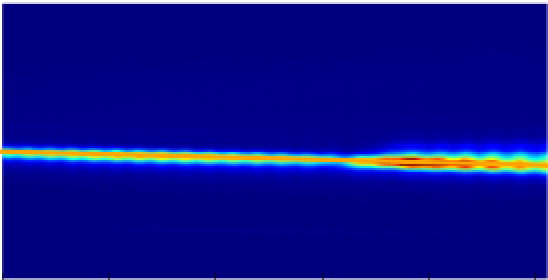

The white light, now "imprinted" with the x-ray pulse, is dispersed by a diffraction grating onto a camera. Here's what the raw signal looks like, typically:

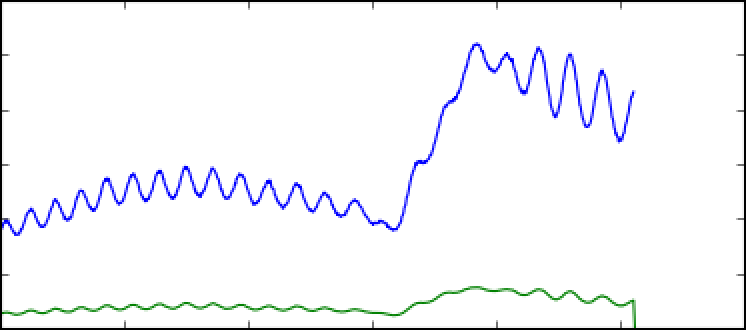

If you take a projection of this image along the y-axis, you obtain a trace similar to this:

The blue line is a raw projection, the green is an ROI'd projection (recommended!). A few things to notice:

- Boom! An edge! The edge moves back and forth on the camera screen depending on the relative time delay between the laser and x-rays.

- Wiggles. The nearly-constant sine-like wave is undesirable background due to an etalon effect inside the TT target. Good analysis will remove it (read on). The etalon is especially bad here – it's amplitude and frequency will depend on the target.

- Limited dynamic range. The edge is big with respect to the camera. The TT has about ~1 ps of dynamic range in a given physical setup. That's fine, because the typical jitter in arrival times between x-rays and laser at LCLS is much less than that. Also, the white light pulse is only ~1 ps long! To change the delay "window" the TT is looking at, a delay stage is used to move the white light in time to keep it matched to the x-rays. It is important, however, to keep an eye on the TT signal and make sure it doesn't drift off the camera!

- Read right-to-left. In this image, the white light arriving before the x-rays is to the right, and following it in time takes us to the left. So time is right to left. Just keeping you on your toes.

Default Analysis: DAQ

Timetool results can be computed by the DAQ while data is being recorded and written directly into the .xtc files. This is almost always done. The DAQ's processing algorithm is quite good, and most users can employ those results without modification. This section will detail how the DAQ's algorithm works, access those results, assess their quality. Even if you are going to eventually implement your own solution, understanding how this analysis works will be useful. Further, in almost all cases, the DAQ results are good enough for online monitoring of the experiment.

How it works

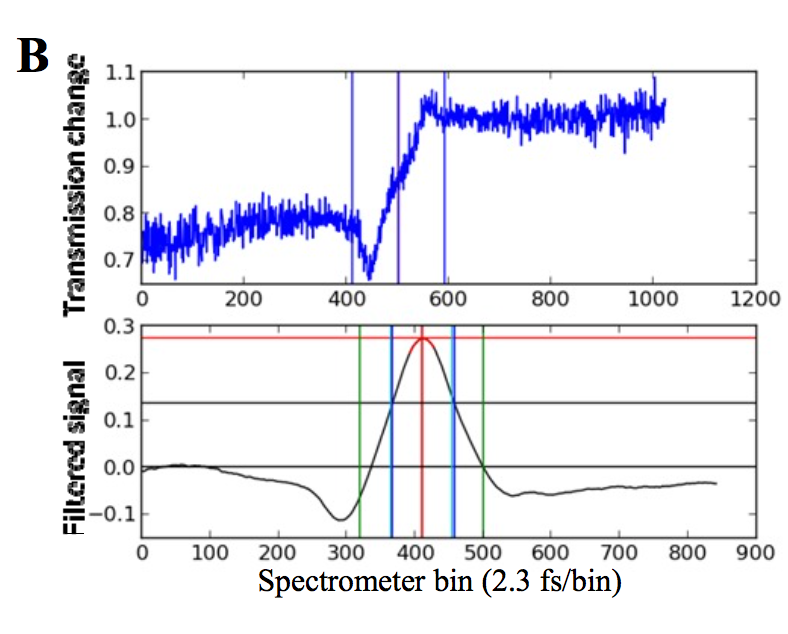

The goal is to find the edge position, the imprint of the x-rays on the white light pulse, along the x-axis of the OPAL camera. To do this, the DAQ uses a matched filter – that means the filter looks just like the expected signal (an edge) and is "translated" across the signal, looking for the x-position of maximal matchy match. More technically: the filter is convoluted with the signal, and the convolution has a peak. That peak is identified as the edge "position" and gives your time signal. Here is an example of a TT trace (top) and the resulting convolution (bottom) used to locate the edge:

The FWHM of the convolution and it's amplitude are good indicators of how well this worked, and are also reported.

The astute reader will notice that this trace has no etalon wiggles. That is because it has been cleaned up by subtracting an x-ray off shot (BYKICK). Those events have the same etalon effect, but no edge – subtracting them removes the etalon. That's a good thing, because the etalon wiggles would have given this method a little trouble if they were big in amplitude.

So, to summarize, here is what the DAQ analysis code does:

- Extract the TT trace using an ROI + projection

- Subtract the most recent x-ray off (BYKICK) trace

- Convolve the trace with a filter

- Report the position, amplitude, FWHM of the resulting peak

The reported position will be in PIXELS. That is not so useful! To convert to femtoseconds, we need to calibrate the TT.

How to get the results

Results can be accessed using the following epics-variables names:

| TTSPEC:FLTPOS | the position of the edge, in pixels |

| TTSPEC:AMPL | amplitude of biggest edge found by the filter |

| TTSPEC:FLTPOSFWHM | the FWHM of the edge, in pixels |

| TTSPEC:AMPLNXT | amplitude of second-biggest edge found by the filter, good for rejecting bad fits |

| TTSPEC:REFAMPL | amplitude of the background "reference" which is subtracted before running the filter algorithm, good for rejecting bad fits |

| TTSPEC:FLTPOS_PS | the position of the edge, in picoseconds, but requires correct calibration constants be put in the DAQ when data is acquired. Few people do this. So be wary. |

These are usually pre-pended by the hutch, so e.g. at XPP they will be "XPP:TTSPEC:FLTPOS". The TT camera (an OPAL) should also be in the datastream.

Here is an example of how to get these values from psana

import psana

ds = psana.MPIDataSource('exp=cxij8816:run=221')

evr = psana.Detector('NoDetector.0:Evr.0')

tt_camera = psana.Detector('Timetool')

tt_pos = psana.Detector('CXI:TTSPEC:FLTPOS')

tt_amp = psana.Detector('CXI:TTSPEC:AMPL')

tt_fwhm = psana.Detector('CXI:TTSPEC:FLTPOSFWHM')

for i,evt in enumerate(ds.events()):

tt_img = tt_camera.raw(evt)

# <...>

How to know it did the right thing

Cool! OK, so how do you now if it worked?

Filtering TT Data

If you make a plot of the measured timetool delay it is quite noisy (e.g. the laser delay vs. the measured filter position, TTSPEC:FLTPOS, while keeping the TT stage stationary). There are many outliers. This can be greatly cleaned up by filtering based on the TT peak.

I (TJ, <tjlane@slac.stanford.edu>) have found the following "vetos" on the data to work well, though they are quite conservative (throw away a decent amount of data). That said they should greatly clean up the TT response and has let me proceed in a "blind" fashion:

Require:

tt_amp [TTSPEC:AMPL] > 0.05 AND

50.0 < tt_fwhm [TTSPEC:FLTPOSFWHM]< 300.0

This was selected based on one experiment (cxii2415, run 65) and cross-validated against another (cxij8816, run 69).

Always Calibrate! Why and How.

Rolling Your Own