Quick Example

To run interactive-psana execute the following commands. This requires the ability to ssh to an LCLS unix account and the ability to open up a graphics window on your computer ("X-windows"). Replace "YOURACCOUNTNAME" in the first line below with your unix account name

ssh -X pslogin.slac.stanford.edu -l YOURACCOUNTNAME ssh -X psana source /reg/g/psdm/etc/ana_env.csh sit_setup cp /reg/g/psdm/tutorials/xcs/ipsana.py ipsana.py python ipsana.py

The 17-line ipsana.py script loops over 4 events and plots a princeton camera image (close each image window to see the next one). You can examine the script with the command "more ipsana.py" or edit it with unix editors like emacs, vim, or vi.

Introduction

This document offers a brief overview of a high-level interface to the psana analysis framework for user applications written in the Python programming language. The interface is informally known as "interactive psana*. The tool's use is not solely limited to the interactive analysis scenarios. It also allows its users to benefit from a rich set of services of the core framework while retaining a full control over an iteration in data sets (runs, files, etc.). This combination makes it possible for the interactive exploration and (if needed) visualization of the experimental data. Note that by the later we always mean data files in the XTC or HDF5 formats produced at the LCLS DAQ or Data Management system. We also suggest visiting the psana - Interactive API which is found in the end of the document.

The following usage scenario represents the core "philosophy" of the interface:

- in order to access a data (from a single file, or a collection of files belonging to a run, or files of multiple runs) a user has to write a Python script. There are no restrictions on how the script is written, or which other Python modules are used by the script.

- in that script the user imports a special module called psana. The module provides an interface to the services of the core framework. The psana module is no different than any other modules imported into the script.

- the user opens a data set using a special function (provided by the module) similarly to opening regular files

- at this point the experimental data (so called events) can be read in a way which is conceptually similar to how data records are read from a regular file

- each such event obtained from the data set is a complex object whose content can be explored by calling various methods returning components of the events as well as various meta-information

- in addition to events the framework also allows access to the event environment information, which incorporates things like EPICS variables, etc.

The rest of the document will map that "philosophy" into practical steps which would need to be taken along that path. We will also cover the basic principles of the psana API as well as their behavioral aspects. Please, keep in mind that the implementation of the interactive psana is based on its core psana. Hence there are many commonalities which are shared by these tools, including:

- the transient Event Model

- the transient Environment Model

- naming convention for detector components

- a collection of Python classes representing detector components

- the job configuration service and the syntax of the configuration files

- modules written for the batch version of psana

The final comment, before we'll proceed to the practical steps, is that a reader of the document isn't required to be fully familiar with the batch framework. Those areas where such knowledge would be needed are expected to be covered by the document. Though, we still encourage our users to spend some time to get an overview of the Data Analysis Tools we provide at PCDS. That's because many problems in doing the data analysis can be solved by the batch version of psana in a more efficient and natural way. These two flavors of the framework are not meant to compete with each other, they are designed to complement each other to cover a broader spectrum of analysis scenarios.

Test data

Setting up the analysis environment

There are two steps which need to be performed in order to get access to this API:

- obtain and properly configure your UNIX account at PCDS. Specific instructions can be found in the Account Setup section of the Analysis Workbook.

select the latest analysis release by running the following command before launching the Python interpreter:

% sit_setup ana-current

The later command should be done just once per session. It will initialize all relevant environment variables, including PATH, LD_LIBRARY_PATH, PYTHONPATH and some others. This will also give you an access to an appropriate version of the Python interpreter and the corresponding Python modules. We recommend using ipython. The following example illustrates how to launch the interpreter and test if the interactive psana module is available in the session environment. When everything is set up correctly one should see:

% ipython Python 2.7.2 (default, Jan 14 2013, 21:09:22) Type "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information. IPython 0.13.1 -- An enhanced Interactive Python. ? -> Introduction and overview of IPython's features. %quickref -> Quick reference. help -> Python's own help system. object? -> Details about 'object', use 'object??' for extra details. In [1]: import psana In [2]: psana. Display all 108 possibilities? (y or n) psana.Acqiris psana.Gsc16ai psana.ndarray_float32_1 psana.ndarray_int32_5 psana.ndarray_uint32_3 psana.Andor psana.Imp psana.ndarray_float32_2 psana.ndarray_int32_6 psana.ndarray_uint32_4 psana.Bld psana.Ipimb psana.ndarray_float32_3 psana.ndarray_int64_1 psana.ndarray_uint32_5 psana.BldInfo psana.Lusi psana.ndarray_float32_4 psana.ndarray_int64_2 psana.ndarray_uint32_6 ..

The first application

Here is the psana version of the traditional "Hello World!" program:

from psana import *

dataset_name = "exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22"

ds = DataSource(dataset_name)

for num,evt in enumerate(ds.events()):

id = evt.get(EventId)

print "Event #",num," has id:",id

The code of this example does nothing but scanning through all events of the data set and reporting identifiers (class EventId) of each event (class Event). The identifiers () encapsulate a number of attributes, including: timestamp, fiducials, etc. And here is how the output should look like:

Event # 0 has id: XtcEventId(run=22, time=2013-01-18 17:58:53.047288760-08, fiducials=19404, ticks=331022, vector=1) Event # 1 has id: XtcEventId(run=22, time=2013-01-18 17:58:53.055622526-08, fiducials=19407, ticks=330630, vector=2) Event # 2 has id: XtcEventId(run=22, time=2013-01-18 17:58:53.063956294-08, fiducials=19410, ticks=329468, vector=3) ..

Now let's go through the example's code line-by-line and see what it does at each step:

importing all definitions from the psanamodule into the global namespace. This includes functions, classes and types:

from psana import *

opening a data set and checking if it exists/available to your process:

dataset_name = "exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22" ds = DataSource(dataset_name)

iterating over all events in the data set and obtaining an event identification object for each event:

for num,evt in enumerate(ds.events()): id = evt.get(EventId)

Please, note that the following definitions mentioned in the example were imported from the psana module:

- DataSource is a function for locating and opening data sets

- Event is type (class) representing transient (in-memory) event objects.

- EventId is actually a type (class) which is used as a primary key to fetch the event identity object from an event.

More details on parameters of the get() function will be provided later in this document. The module exports many other definitions. Some of them will be introduced and explained in the rest of the document as needed.

Data set specification

The data set string encodes various parameters, some of which are needed to locate data files, while others would affect the behavior of the file reader. The general syntax of the string is:

par[=val][:par[=val][...]

These are some of the parameters which are supported in psana:

experiment name (which may optionally contain the name of an instrument)

exp=cxi12313 exp=CXI/cxi12313

run number specification (can be a single run, a range of runs, a series of runs, or a combination of all above):

run=1 run=10-20 run=1,2,3,4 run=1,20-20,31,41

file type (presently the default type is 'xtc')

xtc h5

a random stream (if a value is omitted) or a specific stream. Note this option only makes a sense for XTC files:

one-stream one-stream=2

allow reading from live files while they're still being recorded (by the DAQ or by the Data Migration service). Note that this feature is only available when running psanaat PCDS, in all other cases the option will be ignored:

live

Putting all together one would see a data set specification which would tell the framework to read data of stream #2 from XTC files of run 41 while these files were sill being recorded (by the DAQ, or the data migration service, or by another process of the same user, etc.):

exp=CXI/cxi12313:run=41:xtc:one-stream=2:live

The complete description of the data set string syntax and allowed parameters can be found in the specification document.

Extracting data from an event

In this section we're going to focus on an event object to see how to get various information from it. Let's begin with an example where we're fetching and plotting an image captured at the Princeton camera (which is one of the detectors available at the XCS instrument). In this example we won't be iterating over all events. Only the first event will be considered:

from psana import *

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

src = Source('DetInfo(XcsBeamline.0:Princeton.0)')

itr = ds.events()

evt = itr.next()

frame = evt.get(Princeton.FrameV1, src)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure('Princeton Camera')

plt.imshow(frame.data())

plt.show()

This code introduces two new things which weren't present in the "Hello World" code:

- the get()method is called with two parameters:

- the expected type of an event component

- the expected address (source) of a component within an event

- Princeton.FrameV1 which is a type of the Princeton camera object returned by the get() method

Why should you care about detector/component types?

By looking at how the get() method was invoked in the example one may argue that the component type information isn't really required, and knowing the detector source alone is all one would need here. That's not quite true. A problem is that, for the some detectors (sources) there may be more than one object stored within an event per such detector. Those objects would have different types. Hence the get() method requires at least two (and in some occasions - even three) keys to be provided to tell the method which of those objects to return. More information on this subject will be given in a subsection found below.

The psana event is a data container

The most correct way to perceive the psana event is by treating it as a data container storing pertinent information recorded by the LCLS DAQ system (or later produced by the psana framework modules) in a context of a particular LCLS shot. Note that the framework event object has a transient state. It's up to the psana framework how to initialize this object when reading relevant data from the input files. Moreover, the event is a dynamic container whose contents may change during its life time within an application. More information on the event lifetime will be provided later in this document when discussing external psana modules.

The event allows the following operations (methods):

- get() - fetching components of an event

- put() adding new components to an event

- remove() - removing existing components from an event

- keys() - obtaining a dictionary of components hold by an event

The rest of this chapter will be devoted to explaining formal signatures and behavioral aspects of these methods.

Four forms of the get() method

The psana event contains objects which may have different origins, such as:

- the LCLS DAQ system

- external psana modules (for example the calibrations or frame reconstruction modules)

- the psana framework itself (such as the event identifier)

- the user's code of the interactive psana (the code can use the event's put() method to extend the event before passing it to another algorithm in the workflow/processing pipeline within the same Python application)

Things are getting further complicated by the following factors:

- the DAQ system may produce more than one object for a particular detector, each of which would needed to be unambiguously identified in the event container

- the external psana modules or the interactive Python code may add more versions for the same detector object as a result of data processing (calibration, etc.)

In order to deal with all these object addressing requirements psana introduces three keys which allows to uniquely identify a particular object within the event:

- type - is the primary (mandatory) parameter specifying an expected type of an object within the framework

- src - is some sort of an address of a component within an event. The address parameter is not required for some types of components. Actually, the very first ("Hello World!") example of this Introduction just illustrated it. Technically, the source information is encapsulated into a special object which is produced by the constructor of class Source.

- key - is an optional string which is mainly meant to be used to name various stages of processing for the same kind of a detector (though, it's not really limited to a specific detector).

The combination of these keys led to the following collection of signatures supported by the method:

- get(type, src, key) - the full form of the method

- get(type, src) - the shortcut form of the method which is equivalent to get(type, src, "")

- get(type, key) - is another shortcut which is similar to get(type, Source(None), key)

- get(type) - is the shortest form which is equivalent to get(type, Source(None), "")

The type key is a real Python type known to the framework. All types which would be recognized by a particular version of the framework can be obtained by the 'dot' operator of the ipython interpreter as shown below:

% ipython In [1]: import psana In [2]: psana. Display all 108 possibilities? (y or n) psana.Acqiris psana.Gsc16ai psana.ndarray_float32_1 psana.ndarray_int32_5 psana.ndarray_uint32_3 psana.Andor psana.Imp psana.ndarray_float32_2 psana.ndarray_int32_6 psana.ndarray_uint32_4 psana.Bld psana.Ipimb psana.ndarray_float32_3 psana.ndarray_int64_1 psana.ndarray_uint32_5 psana.BldInfo psana.Lusi psana.ndarray_float32_4 psana.ndarray_int64_2 psana.ndarray_uint32_6 psana.Camera psana.OceanOptics psana.ndarray_float32_5 psana.ndarray_int64_3 psana.ndarray_uint64_1 psana.ControlData psana.Opal1k psana.ndarray_float32_6 psana.ndarray_int64_4 psana.ndarray_uint64_2 psana.CsPad psana.Orca psana.ndarray_float64_1 psana.ndarray_int64_5 psana.ndarray_uint64_3 psana.CsPad2x2 psana.PNCCD psana.ndarray_float64_2 psana.ndarray_int64_6 psana.ndarray_uint64_4 psana.DataSource psana.PSAna psana.ndarray_float64_3 psana.ndarray_int8_1 psana.ndarray_uint64_5 ..

Note that some of those entries aren't really types. Besides, they may be nested Python modules providing more types like this one:

In [3]: psana.Princeton. psana.Princeton.Config psana.Princeton.ConfigV3 psana.Princeton.Frame psana.Princeton.Info psana.Princeton.ConfigV1 psana.Princeton.ConfigV4 psana.Princeton.FrameV1 psana.Princeton.InfoV1 psana.Princeton.ConfigV2 psana.Princeton.ConfigV5 psana.Princeton.FrameV2

Where can I find detailed description of the component types?

One can find an information on the API of each type at the Psana Data Interfaces Reference document.

The second (source) key should be constructed using a special class called Source which also exported by the psana module:

src = Source('<object address string>')

The format of the object address string varies between different kinds of objects, and in general it's related to an origin of a desired object.

And the last key is an optional string which is called key. Its primary use is to disambiguate between different versions of the same kind of information within the event. In the current practice raw data which originate from the DAQ system would always have this key empty. If there is an external psana module processing that raw data and turning it in some more convenient to use form (calibrated, reconstructed, reduced, restructured, etc.) then that second version would get some non-trivial key value, like: "v1", "processed", "calibrated", etc. A specific name of the key is solely under a discretion of the corresponding module (user's code). The combinations of types, sources and keys allows users to build very powerful workflows on top of psana.

The ipython interpreter makes it easy to explore the namespace of the framework module to see what's available. This unfortunately doesn't address the question - "Now, as I have my event, how do I know what's in that event, which form of the get() method should I use, and which specific values of parameters should I put? Unless you already know the answer, proceed to the next section to find the one!

Browsing through a catalog of objects stored within an event

The following example demonstrates how to dump a catalog of event components:

In [8]: evt.keys() Out[8]: [EventKey(type=psana.EvrData.DataV3, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Camera.FrameV1, src='DetInfo(CxiDg1.0:Tm6740.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Camera.FrameV1, src='DetInfo(CxiDg2.0:Tm6740.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.CsPad.DataV1, src='DetInfo(CxiDs1.0:Cspad.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Bld.BldDataEBeamV3, src='BldInfo(EBeam)'), EventKey(type=psana.Bld.BldDataFEEGasDetEnergy, src='BldInfo(FEEGasDetEnergy)'), EventKey(type=psana.EventId), EventKey(type=None)] In [9]:

The information reported by the method would give us an idea what's found in the event, and how to obtain those components using the get() method. When psana has been imported into the global namespace, the mapping is:

from psana import *

...

obj1 = evt.get( EvrData.DataV3, Source('DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.0)'))

obj2 = evt.get( Camera.FrameV1, Source('DetInfo(CxiDg1.0:Tm6740.0)'))

obj3 = evt.get( Camera.FrameV1, Source('DetInfo(CxiDg2.0:Tm6740.0)'))

obj4 = evt.get( CsPad.DataV1, Source('DetInfo(CxiDs1.0:Cspad.0)'))

obj5 = evt.get( Bld.BldDataEBeamV3, Source('BldInfo(EBeam)'))

obj6 = evt.get( Bld.BldDataFEEGasDetEnergy, Source('BldInfo(FEEGasDetEnergy)'))

obj7 = evt.get( EventId)

Few notes on that output:

- the last component (the one which has type=None) reported by the keys() method should be ignored. This is an artifact of the current implementation of this API. It may go away in some future release of the software. We mention it here just to address possible confusion which users may have when seeing this output.

- note the variations in the syntax of the components' addresses.

Working with a list of keys

For those would like to build some automation in discovering which components and of what kind exist in the event there is another option. A user can iterate over the list of key elements to examine their attributes. Each such element would encapsulate a type, a source and a key (string) of the corresponding event component. Consider the following example:

for k in evt.keys():

print "type: ", k.type()

print "source: ", k.src()

print "key: ", k.key()

..

The type() method will return one of those Python type objects which were already mentioned in section "Four forms of the get() method". If a user is looking for a key which has a specific type then the following type comparison can be used:

for k in evt.keys():

if k.type() == Camera.FrameV1:

print "got Camera.FrameV1"

The src() method would return an object of class Src which is an abstraction (base class) for specific classes of data sources. At the time when this document was being written, there were three kinds of sources:

- detector-level addresses (class DetInfo)

- addresses for BLD devices (class BldInfo)

- event processing information (class ProcInfo)

Since APIs of those specific source classes differ one from another then a user would need to obtain the final type using the following technique:

for k in evt.keys():

src = k.src()

src_type = type(src)

if src_type == DetInfo : print "detector name: ", src.detName(), " device name: ", src.devName(), ...

elif src_type == BldInfo : print "detector type: ", src.type(), " detector name: ", src.detName(), ...

elif src_type == ProcInfo : print "IP address: ", src.ipAddr(), " process id: ", src.processId()

Look for the documentation of the source classes to get a full description of the classes' methods.

Finally, the last method key() returns a string representing an optional third key which was already explained in section "Four forms of the get() method". In most cases the method will return an empty string.

Other operations with events

The event object also provides two operations for manipulating the contents of the event: adding more or removing existing components. Signatures of both operations are very similar to the ones of method get(). Specifically these are four forms of method remove():

- remove(type, src, key) - the full form of the method

- remove(type, src) - the shortcut form of the method which is equivalent to remove(type, src, "")

- remove(type, key) - is another shortcut which is similar to remove(type, Source(None), key)

- remove(type) - is the shortest form which is equivalent to remove(type, Source(None), "")

And similar forms for method put():

- put(obj, type, src, key) - the full form of the method

- put(obj, type, src) - the shortcut form of the method which is equivalent to put(obj, type, src, "")

- put(obj, type, key) - is another shortcut which is similar to put(obj, type, Source(None), key)

- put(obj, type) - is the shortest form which is equivalent to put(obj, type, Source(None), "")

Note that method put() has an additional parameter for a new object which is expected to be added to the event.

And the last method of the event API will return a run number. This information may be useful for data sets spanning across many runs:

ds = DataSource("exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22,23,24,25)

for evt in ds.events():

print "run: ", evt.run()

..

Accessing event environment data

The event environment encapsulate a broad spectrum of data and services which have various origins. This environment is needed to evaluate or process event data in a proper context. Some of these data may have different life cycles than events. Other parts of this information (such as calibrations) may not even come directly from the input data stream (the DAQ system). The information is available through a special object which is obtained by calling the data set object's method env():

dsname = 'exp=MEC/mec70813:run=35' ds = DataSource(dsname) env = ds.env() env. env.calibDir env.configStore env.expNum env.fwkName env.hmgr env.jobName env.calibStore env.epicsStore env.experiment env.getConfig env.instrument env.subprocess

The same environment object can also be obtained by calling a similar method of classes Run.env() and Step.env(). The environment can be split into a number of categories which are explained in a dedicated sub-subsection below.

Job configuration information

Methods found in this category are meant to be used for information purposes. Though, one of their practical uses could be to create output (log, data, etc.) files which would have unique yet meaningful names relevant to an input data set and a job processing the data:

- expNum(): a numeric identifier of the corresponding experiment

- experiment(): the name of the experiment

- jobName(): the unique name of the job (this may be used by the users code to create output log files which would have unique yet meaningful names)

- subprocess(): the process number in a multi-process version of the framework (at the moment the method will always return 0. See details at section "Parallel data processing")

- instrument(): the name of the instrument

This is a sample analysis session illustrating a result of calling the methods:

ds = DataSource('exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22')

env = ds.env()

print ' framework name:',env.fwkName()

print ' job name:',env.jobName()

print ' instrument:',env.instrument()

print ' experiment id:',env.expNum()

print ' experiment name:',env.experiment()

print 'subprocess number:',env.subprocess()

This will produce an an output which will look like this:

framework name: psana

job name: cxitut13:run=22

instrument: CXI

experiment id: 304

experiment name: cxitut13

subprocess number: 0

Calibration Store

There are two methods in this category:

- calibDir(): the path name to a directory with calibration constants

- calibStore(): the interface to a repository of the calibration constants

The second method would return an object of the generic environment container class EnvObjectStore . Specific details of this interface are beyond a scope of the present document. The Calibration Store is mainly used by special calibration modules.

Configuration Store

This Store encapsulate various detector/device configuration information which is typically (in reality - it may vary) recorded by the DAQ system at the beginning of each run.

Read carefully before trying the next example

The configuration information (as well as most of the environment) is loaded after at least one event was read from an input data set. Otherwise the configuration store would be empty. To demonstrate this effect the example is making two attempts to dump configuration keys - one before, and the other one - after getting to the first event.

Consider the following example in which the first try to list configuration keys will result in an empty dictionary:

ds = DataSource('exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22')

configStore = ds.env().configStore()

configStore.keys()

[]

The second attempt made after getting to the first event will produce some meaningful output:

itr = ds.events() evt = itr.next() configStore.keys() [EventKey(type=psana.ControlData.ConfigV2, src='ProcInfo(0.0.0.0, pid=17877)'), EventKey(type=None, src='ProcInfo(0.0.0.0, pid=17877)'), EventKey(type=psana.EvrData.ConfigV7, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.0)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.EvrData.ConfigV7, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.1)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.1)'), EventKey(type=psana.EvrData.ConfigV7, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.2)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.2)'), EventKey(type=psana.Epics.ConfigV1, src='DetInfo(EpicsArch.0:NoDevice.0)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(EpicsArch.0:NoDevice.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Epics.ConfigV1, src='DetInfo(EpicsArch.0:NoDevice.1)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(EpicsArch.0:NoDevice.1)'), EventKey(type=psana.Acqiris.ConfigV1, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Acqiris.0)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Acqiris.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Ipimb.ConfigV2, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Ipimb.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Lusi.IpmFexConfigV2, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Ipimb.0)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Ipimb.0)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Ipimb.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Camera.FrameFexConfigV1, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Opal4000.1)'), EventKey(type=psana.Opal1k.ConfigV1, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Opal4000.1)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Opal4000.1)'), EventKey(type=None, src='DetInfo(CxiEndstation.0:Opal4000.1)'), EventKey(type=psana.Ipimb.ConfigV2, src='DetInfo(CxiDg1.0:Ipimb.0)'), EventKey(type=psana.Lusi.IpmFexConfigV2, src='DetInfo(CxiDg1.0:Ipimb.0)'), ..

The configuration keys have a structure which is reminiscent to the one of the event keys. This is illustrated below:

In [140]: configStore.

configStore.get configStore.keys

In [142]: keys = configStore.keys()

In [143]: keys[4]

Out[143]: EventKey(type=psana.EvrData.ConfigV7, src='DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.1)')

In [144]: keys[4].type()

Out[144]: psana.EvrData.ConfigV7

In [145]: obj = configStore.get(EvrData.ConfigV7,Source('DetInfo(NoDetector.0:Evr.1)'))

In [146]: obj.

obj.eventcodes obj.neventcodes obj.noutputs obj.npulses obj.output_maps obj.pulses obj.seq_config

In [147]: type(obj)

Out[147]: psana.EvrData.ConfigV7

The get() method of the Configuration Store will return objects describing the corresponding components of the events. The configuration objects are explained in "The psana Reference Manual". As an example, here is a direct link to the documentation of class EvrData.ConfigV7.

ControlPV

ControlPV is a configuration data which is updated on every step (steps are explained later in the document when discussing various ways of iterating over events in a data set). Like any other configuration data it is accessible through the environment object. Here is an example of getting controlPV data:

from psana import *

ds = DataSource('exp=xpp66613:run=300:h5')

for step in ds.steps():

control = ds.env().configStore().get(ControlData.Config)

print [(c.name(), c.value()) for c in control.pvControls()]

This will result in the following output:

[('lxt_ttc', -1.9981747581849466e-12)]

[('lxt_ttc', -1.8004943676675365e-12)]

[('lxt_ttc', -1.6001426205245978e-12)]

[('lxt_ttc', -1.3997908733800049e-12)]

[('lxt_ttc', -1.199439126235412e-12)]

[('lxt_ttc', -9.990873790924733e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', -7.987356319478803e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', -5.983838848049417e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', -3.9803213766034873e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', -2.0035174714459297e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', 0.0)]

[('lxt_ttc', 2.0035174714459297e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', 4.007034942875316e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', 6.010552414321246e-13)]

[('lxt_ttc', 8.014069885767175e-13)]

..

EPICS Store

All EPICS variables can be accessed through the EpicsStore object of the environment:

ds = DataSource(dsname) epics = ds.env().epicsStore() epics. epics.alias epics.aliases epics.getPV epics.names epics.pvName epics.pvNames epics.status epics.value

The store interface allows:

- obtaining official PV names of the EPICS variables (method pvNames()). These names are often obscure.

- obtaining alias names which are known to the store (method aliases()). Aliases are experiment-dependent simpler names specified by the users at the time the data is taken.

- method names() shows both the aliases and the pvNames

- return the alias for specified PV name (method alias()), or vice-versa (method pvName())

- obtaining values of PVs (method value()). This method can accept either a name or an alias.

- obtaining descriptor objects for PVs (method getPV()). This is useful for understanding the type/shape of the epics data, for example.

How to properly use the EPICS store

It's important to understand that the contents of the store is relevant to the most recent event obtained from a data set. This means that:

- the store will contain the configuration pv's after a data set has been just opened and no single event has been fetched from it

- the contents of the store will change from one event to the other one

Therefore it's up to a user code to implement a correct logic for fetching events and EPICS variables to ensure that they're properly synchronized.

Here is a code which would be tracking values of some PV for all events and reporting events when the value of the PV changes. Notice that values of this (which is also true for most EPICS variables) won't change at each event:

ds = DataSource(dsname)

epics = ds.env().epicsStore()

prev_val = None

for i, evt in enumerate(ds.events()):

val = epics.value('LAS:FS0:ACOU:amp_rf1_17_2:rd')

if val != prev_val:

print "%6d:" % i, val

prev_val = val

0: 2016

725: 2024

845: 2019

966: 2014

1932: 2021

2053: 2020

2174: 2016

3381: 2020

3502: 2024

4830: 2018

6279: 2019

6400: 2018

7728: 2023

7849: 2019

9177: 2016

10626: 2021

10747: 2022

12075: 2016

13524: 2020

..

Configuration pv's refer to EPIC's ctrl headers. These are not often used for analysis and all EPICS pv's should be replaced by event data after the first event is fetched. However we have seen a few cases where a ctrl pv was not replaced immediately. These issues have been resolved for future runs, but to be careful, one could rewrite the main loop as follows:

for i, evt in enumerate(ds.events()):

pv = epics.getPV('LAS:FS0:ACOU:amp_rf1_17_2:rd')

if pv.isCtrl():

print "warning: pv is still ctrl as of event %d, may be known or new bug" % i

continue

val = pv.value(0)

Services

The Histogram Manager is the only public (user-level) service which is implemented in the current version of the framework. A reference to the manager can be obtain using:

ds = DataSource('exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22')

hist_manager = ds.env().hmgr()

Iterating over events, steps, runs

The previous examples have already demonstrated the very basic technique for finding all events in a data set. The interactive psana has actually more elaborate ways of browsing through the data:

iterating over all events of a dataset:

ds = DataSource(...) for evt in ds.events(): ...

iterating over all runs of a dataset, then iterating over all events of each run:

ds = DataSource('exp=...:run=12,13,14') for run in ds.runs(): for evt in run.events(): ...

iterating over all runs of a dataset, then iterating over all steps of each runs, then iterating over all events of each step:

ds = DataSource('exp=...:run=12,13,14') for run in ds.runs(): for step in run.steps(): for evt in step.events(): ...

iterating directly over all steps of a dataset, then iterating over all events of each step:

ds = DataSource('exp=...:run=12,13,14') for step in ds.steps(): for evt in step.events(): ...

From the performance point of view all methods are equal to each other. A choice of a particular technique depends on specific needs of a user application. Also note that intermediate objects which will be exposed during these iterations may have additional methods. More information on those can be found at the external documentation:

Using modules written for the batch psana

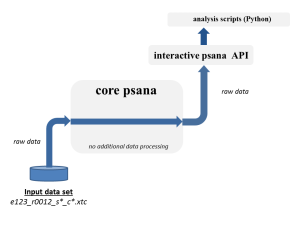

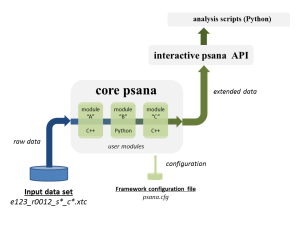

One of the features (benefits) of the interactive psana is that it allows to reuse algorithms which are written as modules for the batch psana. The concept of the modules is explained in details in the Psana User Manual. Here is a simplified architecture of the framework and a data flow between its various components. The first diagram shows using interctive psana w/o any external modules, and the second one - with 3 sample modules doing some additional data transformation/processing on the events:

From a prospective of the interactive psana users, each event read from an input data set will have to go first through a chain of modules before finally getting to the user's script. The events may be modified/extended by the modules as they'll be going along this path. This mechanism is opening a number of interesting possibilities:

- extending an event with derived (processed) data before it will get to the user

- collecting various statistics on the data orthogonal to the top-level analysis algorithm

- combining heavy-weight data processing (by means of the base framework modules written in C++) with the data visualization at the Python framework level

All of this together with a flexibility of the top-level (interactive) Python scripts allows to build rather powerful data processing/analysis workflows (pipelines, etc.).

However users should be also aware (careful) about certain limitations of the technique in the present version of the framework:

- skipping (filtering) events by the modules won't work. The Python code will be receiving all events read from an input data set.

- re-opening the same data set will result in a complete restart in the internal state of psana modules as if they were run in a separate job after the re-opening.

The rest of this chapter will provide a brief introduction into how to turn on and use the feature in the framework.

Configuring psana to use external modules

External modules are activated in the framework by mean of a specially prepared configuration file which has to be given to the framework before opening a data set. Otherwise the file won't make any effect. Here is this example:

cfg = "/reg/g/psdm/tutorials/cxi/cspad_imaging/frame_reco.cfg"

setConfigFile(cfg)

ds = DataSource('exp=CXI/cxitut13:run=22')

Also note that the core psana also allows an optional data set specification to be placed into the configuration files. This specification will be ignored by the interactive psana where the data set is required to be explicitly passed into function DataSource() as a positional parameter. Please, read the Psana User Manual for further instructions on how to write the configuration files.

Where can I find a list of existing *psana* modules?

There are two documents which you may want to explore:

- psana - Module Catalog - comprehensive catalog of psana modules in the latest Analysis Release

- psana - Module Examples

Calibration modules example: re-contracting a full CSPad image

In this section we're going to explore in a little bit more details the effect of the configuration file which was used in the previous. First, let's have a look at the contents of that file:

[psana] verbose = 0 modules = CSPadPixCoords.CSPadImageProducer [CSPadPixCoords.CSPadImageProducer] source = CxiDs1.0:Cspad.0 typeGroupName = CsPad::CalibV1 key = imgkey = reconstructed tiltIsApplied = true print_bits = 0

This configuration refers to some real module (CSPadImageProducer from the OFFLINE Analysis package CSPadPixCoords) which will be doing the geometric reconstruction of the full CSPad image. This module is a part of any latest analysis releases. The main effect of the module is that it will extend each event by an additional component which otherwise wouldn't be present in the event (look for the first one in the output below):

evt.keys() .. EventKey(type=psana.ndarray_int16_2, src='DetInfo(CxiDs1.0:Cspad.0)', key='reconstructed'), .. EventKey(type=psana.CsPad.DataV2, src='DetInfo(CxiDsd.0:Cspad.0)'), ..

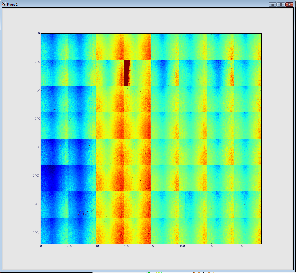

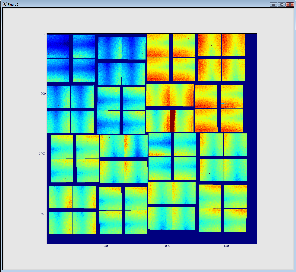

That component has an additional key='reconstructed' (please, refer back to the section on the Four forms of the get() method for more information on that parameter). An object returned with that key has a type of a 2D array of 16-bit elements representing CSPad pixels. With a little bit of help from Matplotlib one can easily turn this into an image. The next example will illustrate how to show both raw (unprocessed) and reconstructed version of the CSPad image:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure()

plt.ion()

plt.show()

cspad = evt.get(CsPad.DataV2,Source('DetInfo(CxiDs1.0:Cspad.0)'))

a = []

for i in range(0,4):

quad = cspad.quads(i)

d = quad.data()

a.append(np.vstack([d[i] for i in range(0,8)]))

frame_raw = np.hstack(a)

frame_reconstructed = evt.get(ndarray_int16_2,Source('DetInfo(CxiDs1.0:Cspad.0)'),'reconstructed')

plt.imshow(frame_raw)

plt.clim(850,1200)

plt.imshow(frame_reconstructed)

plt.clim(850,1200)

The result is shown below. The first (on the left) image represents 32 so called 2x1 CSpad elements stacked into a 2D array. The second images represents a geometrically correct (including relative alignment of the elements) frame:

Advanced techniques

Random Access to XTC Files ("Indexing")

LCLS runs which have XTC index files (generated by the DAQ) can have their events accessed in non-sequential order. The associated EPICS variables and beginCalib information is correctly provided by psana. You can check for the existence of these files by substituting your experiment name in a command similar to:

ls /reg/d/psdm/XCS/xcs84213/xtc/index/

There should be 1 index file per data file in your experiment. If they do not exist, they can be created using an "xtcindex" command (send email to "pcds-help@slac.stanford.edu" to have this done).

import psana

# note the "idx" input source at the end of this line: indicates that events will be accessed randomly.

ds = psana.DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15:idx')

for run in ds.runs():

# get array of timestamps of events

times = run.times()

for i in range(3,-1,-1):

#request a particular timestamp in a run

evt=run.event(times[i])

if evt is None:

print '*** event fetch failed'

continue

id = evt.get(psana.EventId)

print 'Fiducials:',id.fiducials()

Some notes about indexing:

- If you have a list of timestamps for some other analysis, those can be used in the run.event() method without using the run.times() method.

- Index files are only made available by the DAQ at the end of the run, so can be used before then (this makes "realtime" FFB/shared-memory analysis impossible.

- Indexing only currently works with XTC files (no HDF5 support)

- Currently, indexing only has information about one run at a time (one cannot easily jump between events in different runs).

MPI Parallelization

Using the above indexing feature, it is possible to use MPI to have psana analyze events in parallel (this is useful for many, but not all, algorithms) by having different cores access different events. This can work for offline analysis (on "thousands" of cores) or online analysis from shared memory (up to the number of cores in a monitoring node). For technical reasons, it does not work for online-FFB analysis. This is some sample code that sums a few images in a run in parallel:

mport psana

import numpy as np

import sys

sys.path.insert(1,'/reg/common/package/mpi4py/mpi4py-1.3.1/install/lib/python')

from mpi4py import MPI

comm = MPI.COMM_WORLD

rank = comm.Get_rank()

size = comm.Get_size()

ds = psana.DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15:idx')

src = psana.Source('DetInfo(XcsBeamline.0:Princeton.0)')

maxEventsPerNode=2

for run in ds.runs():

times = run.times()

mylength = len(times)/size

if mylength>maxEventsPerNode: mylength=maxEventsPerNode

# this line selects a subset of events, so each cpu-core ("rank") works on a separate set of events

mytimes= times[rank*mylength:(rank+1)*mylength]

for i in range(mylength):

evt = run.event(mytimes[i])

if evt is None:

print '*** event fetch failed'

continue

cam = evt.get(psana.Princeton.FrameV1,src)

if cam is None:

print '*** failed to get cam'

continue

if 'sum' in locals():

sum+=cam.data()

else:

sum=cam.data()

id = evt.get(psana.EventId)

print 'rank',rank,'analyzed event with fiducials',id.fiducials()

print 'image:\n',cam.data()

sumall = np.empty_like(sum)

#sum the images across mpi cores

comm.Reduce(sum,sumall)

if rank==0:

print 'sum is:\n',sumall

This can be run interactively parallelizing over 2 cores with these commands on a psana node:

setenv PATH /reg/common/package/openmpi/openmpi-1.8/install/bin/:${PATH}

mpirun -n 2 python mpi.py

or run in a batch job:

setenv PATH /reg/common/package/openmpi/openmpi-1.8/install/bin/:${PATH}

bsub -a mympi -n 2 -o mpi.log -q psfehmpiq python mpi.py

Re-opening data sets, opening multiple data sets simultaneously

The underlying implementation of the psana framework would create a separate instance of the framework upon each successful call to function DataSource(). This opens two possibilities:

- having many data sets open at a time. All iterations within each instance will be totally independent from others

- re-opening the same dataset. This technique may be useful in case if one wanted to restart the iterators and to start over exploring a data set. Just be careful about the memory management. Python is a dynamic language which has its own garbage collection for objects. Hence if the user code stored (for example - event) references from a prior attempt to open the same dataset then the original instance of the framework will be still around in a process's memory. Under certain circumstances this may result in memory leaks.

The only caveat with making multiple calls to the DataSource() method is that the very last call to the setConfigFile() operation will affect any instances of the framework open with DataSource(). In other words, an order in which functions setConfigFile() and DataSource() does matter. Consider the following example:

ds1 = DataSource(dsname1) ## no configuration is assumed

setConfigFile('c1.cfg')

ds2 = DataSource(dsname2) ## the dataset will be processed with c1.cfg

ds3 = DataSource(dsname3) ## the dataset will be also processed with c1.cfg

setConfigFile('c2.cfg')

ds4 = DataSource(dsname4) ## the dataset will be processed with c2.cfg

...

Re-opening a dataset is no different from opening multiple different data sets:

ds = DataSource(dsname)

for evt in ds.events():

...

ds = DataSource(dsname) ## this is a fresh dataset object in which

## all iterators are poised to the very first event (run, step)

Working with many events at a time

Be aware about side effects of this technique

Python is a dynamic language which has its the "garbage collection" machinery which will decide when objects can be deleted. Objects will become eligible for the deletion only after the last reference to an object will disappear. Storing objects in a collection (or as members of other objects) may prevent this from happening. Therefore use the techniques explained in the rest of this section with extreme caution, always know what you're doing with objects, and try not to accumulate too many objects in memory without a good reason to do so. In any case, be prepared that your application may run out of memory. In an extreme case if you still choose to load all events of a dataset into an application's memory then a "rule of thumb" here would be to check if a size of your dataset doesn't exceed the total amount of memory available to your application.

Unlike its batch version, the interactive psana allows multiple events to be present at a time within the process memory. Consider the following extreme scenario:

ds = DataSource(dsname) events = [evt for evt in ds.events()] ## Now all events are in memory, hence they can be addressed directly ## from the list evt = events[123] print evt.run()

However, if you aren't so lucky, and a machine doesn't have enough memory then you would see the run-time exception:

RuntimeError: St9bad_alloc

The second thing to worry about is to make sure all relevant environment data are properly handled. In particular, the event environment objects should be obtained and stored along with each cached event at the same time the event object is retrieved from a dataset and before moving to the next event. The problem was already mentioned in this document when discussing the EPICS Store. As an illustration, let's suppose we need to compare images stored in each pair of consecutive events for all events in a run, and to do the comparison we also need the corresponding values of some PV. In that case the correct algorithm may look like this:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

epics = ds.env().epicsStore()

prev_evt = None

prev_pv = None

for evt in ds.events()

pv = epics.value('LAS:FS0:ACOU:amp_rf1_17_2:rd')

if prev_evt is not None:

... ## compare (prev_evt,pv) vs (evt,pv)

prev_evt = evt

prev_pv = pv

Performance/memory considerations

Caching psana.Source()

Consider the following example:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

for evt in ds.events():

frame = evt.get(Princeton.FrameV1, Source('DetInfo(XcsBeamline.0:Princeton.0)'))

..

One problem with that code is that it would construct the component address object (using Source()) at every single step of the iteration. This may cost you some slowdown in your application's performance due to an overhead of parsing the address string and constructing a new source object at each step of the iteration. That won't be necessary, and the example can be easily rewritten like:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

src = Source('DetInfo(XcsBeamline.0:Princeton.0)')

for evt in ds.events():

frame = evt.get(Princeton.FrameV1, src)

..

The cost of accessing detector components

The internal implementation of psana won't fully construct components of an event unless they are requested by a user's code. This will make the following code less efficient when fetching only those components which are actually needed by an application:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

for evt in ds.events():

dets = [evt.get(k.type(),k.src()) for k in evt.keys() if (k.type() != EventId) and (k.type() != None)]

# now all component objects are stored in the list

...

Another reason why we wouldn't generally recommend this technique (though, we understand it may be quite handy in some cases) is that at some future version of the framework event components may be dynamically loaded from disk into memory. Therefore touching components w/o a good reason may not only incur more CPU usage (to construct object), but it may also incur the higher latency to load data due to extra I/O operations.

XTC vs HDF5

In those cases when the same data set is available in both XTC and HDF5 formats, a choice which one to use may be determined by differences in framework performance for these formats. Although being semantically equal, experimental data stored in XTC and HDF5 formats have fundamentally different internal organization. These differences allows for certain (non-overlapping between formats) optimizations when reading data from files. Leaving apart various details, the differences can be summarized as:

- in XTC files data are stored sequentially, one event after another. And each event is stored as a large data record which can be many MB in size. Hence accessing a tiny bit of information from a particular event is not possible without reading the whole event into memory. This makes the XTC format the best choice for sequential reading of events from which all (or a significant fraction) of an event is needed by an application.

- in contrast with that, data in HDF5 files are split into separate areas within a file so that the data of the same kind (say, an EPICS variable) are clustered together in an adjacent locations of the file. This makes the format more suitable for traversing all events of a dataset when a task is to fetch a small (of the same kind) component of each event.

- another distinct feature of the HDF5 format is that allows a direct access to its contents. Although this feature isn't directly utilized by the framework to allow a direct access to events via the framework's API, it still opens a possibility of a more efficient iterations of over events in a dataset. That benefit has only a limited use, but for some applications it may be critical.

Here follows a few examples which illustrate which format works better for specific access pattern.

Reading images for all events of a dataset is better to be done with the XTC format:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

src = Source('DetInfo(XcsBeamline.0:Princeton.0)')

for evt in ds.events():

frame = evt.get(Princeton.FrameV1, src)

..

Reading EPICS variables for all events of a dataset is better to be done with the HDF5 format:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15:h5')

epics = ds.env().epicsStore()

for evt in ds.events()

pv = epics.value('LAS:FS0:ACOU:amp_rf1_17_2:rd')

...

Iterating over the first event of each step is better to be done with the HDF5 format. This is actually a very good example where the direct access to events helps to avoid unnecessary I/O operations when jumping between steps. And obviously, this benefit will only be seen in those datasets which have many steps:

ds = DataSource('exp=XCS/xcstut13:run=15')

for step in ds.steps():

itr = step.events()

evt = itr.next() ## do something about this event and then proceed

.. ## to the next step

These recipes won't cover all possible data access scenarios. But we hope they will give a reader an idea where to look further.

The essential functionality which is not implemented in psana

Data exchange between external psana modules and Python code

Some of our readers may not even recognize that such problem exists, and what it means. In order to illustrate it, consider the following scenario:

- Let's suppose we have an external module written in C++ for the core psana framework.

- That module would process a waveform extracted from an Acqiris detector and translate it into some custom C++ histogram object. This object is put into the event using the previously explained get() method.

- Then in the same configuration of the user processing workflow there is another module written in C++ which would consume that histogram and use it on its stage of he even processing. That second module would use event's get() method to fetch the histogram.

- Now, another user, after learning about this "such easy to use* interactive psana wants to benefit from what's been done by the first user and fetch the histogram object from the event using the get() method into their Python code. And that's where ("Oops!*) the problem shows itself up.

The problem originates from a fact that C++ and Python are two completely different languages having very different object (and memory models). Types which are known in a scope of the C++ module have nothing to do with the ones of the second user's Python code. Unfortunately, there is no generic (which would work for any possible types) solution. The current psana implementation only supports the following types:

- primitive data types: char, bool, integer, float

- string

- NDArray (translates into NumPy array in Python) for primitive data types and strings

Any other types are not supported.

APPENDIX

Glossary of Terms

Here is an explanation of terms which are used throughout the document. Some of them have a specific meaning in a context of the Framework and its API:

- data set (or dataset) - a collection of files associated with a run or many runs

- event - a collection of information associated with a particular X-Ray shot at LCLS. Please, note that event is also a Python object in psana.

- environment (or event environment) - a collection of supplementary information which is needed to interpret event data in the right context. It includes: the latest state of the EPICS variables at a time when the event was recorded by the DAQ system, the DAQ configuration information, the calibrations for the instrument's detectors.

- run - a continuous period of time when the DAQ system was running and recording data.

- step (or Calibration Cycle) - an interval within a run when certain experimental environment was stable (such as motor positions, temperatures, etc.)

- detector - a measuring device within an LCLS instrument. This is just a generalization for sensors, diodes, cameras, etc. Can be also known in this document as an event component.

- data source - is an object withing the framework's event representing a particular detector

- XTC - is a raw data format for files produced by the LCLS DAQ system. The information is stored in these files sequentially. This implies certain limitation on how various data can be extracted from the files. The files have extension of '.xtc'.

- HDF5 - is a portable data format for files which are produced as a result of translating the raw XTC files. The files have extension of '.h5'.

References

- Introduction into PCDS Computing

- Choosing the Analysis Framework

- An overview of the psana framework

- The reference manual for the core classes

- The reference manual for the data classes

- psana - Module Catalog - comprehensive catalog of psana modules in the latest Analysis Release

- psana - Module Examples