...

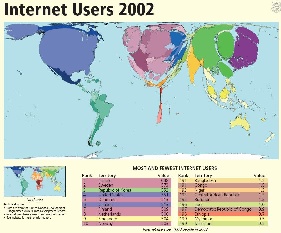

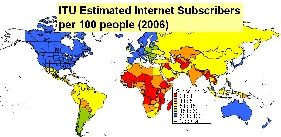

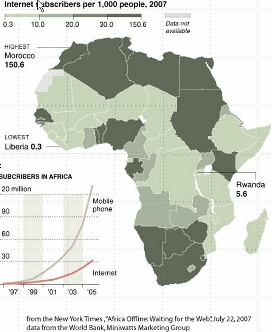

Another way of looking at the poor situation in Africa is to look at Figure 1110, illustrating the lack of Internet users in Africa compared to the rest of the world. At the bottom left of figure 10c is shown the growth of Internet users and cell phone subscribers. This may suggest that cell phone infrastructure may be a very valuable way to leverage Internet growth.

Figure 11a10a: | Figure 11b10b: | Figure 11c10c: |

|---|---|---|

| |

|

Capacity

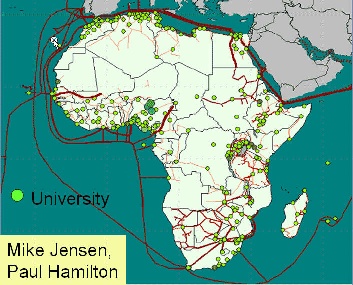

International capacity to African countries is mainly provided via satellite or via fibre links. Satellite links are not only much more expensive (300-1000 times) in terms of $/Mbps but they also induce long delays of over 400mseconds that result in lack of interactivity and poor performance. However in 2004 only 14 of 49 sub-Saharan countries had access to fibre according to NEPAD. In fact as seen in Figure 1211:

Figure 1211: Fibre links to and within Africa and the locations of universities | Figure 1312: |

|---|---|

|

|

There is only one large-scale intercontinental fibre fiber link to Sub-Saharan Africa (SAT-3/WASC/SAFE) which provides connections to Europe (via Portugal) and the Far East for eight countries (Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon and Angola) along the West Coast of the Continent and south to the Cape in South Africa. A second segment, in the Indian Ocean, connects South Africa to Malaysia while passing through Mauritius and India (SAFE). Jointly funded by 36 members and spearheaded by South African Telkom which invested US$85 million for a 13 per cent stake, the project cost about US$650 million dollars. The ownership of the cable was established as a club consortium, which is a confidential shareholder agreement about which little is known (despite efforts by the South African government to release the details). The cable was expected to lead to much reduced international bandwidth costs, but so far this has not occurred due to the business models used to develop the project. Even the few countries that have access to international fibre fiber through SAT-3 are not seeing the benefits because it is operated as a consortium where connections are charged at monopoly prices by the state owned operators which still predominate in most of Africa, and in many other developing regions. Landlocked African operators who have tried to purchase international fibre capacity directly from one of the consortium's international members have found themselves being charged as much to reach the SAT-3 landing point as they were charged to get from the landing station to Portugal. Sadly, the high costs have made it cheaper to send the traffic directly by satellite, even for SAT-3 shareholders such as Telecom Namibia, which has no landing point of its own. Except for some onward links from South Africa to its neighboursneighbors, and from Sudan to Egypt and from Senegal to Mali, the remaining 33 African countries are unconnected to the global optical backbones, and depend on the much more limited and high-cost bandwidth from satellite links.

Mike Jensen

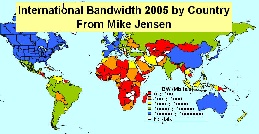

In fact SAT-3 prices have barely come down since it began operating in 2002 and are sold at satellite prices of $4-8K/Mbps/mo even though the capacity is only 5% used. As a result the lack of fibre fiber and lack of competition on SAT-2, international bandwidth to African countries, as seen in Figure 13 12 lags well behind most of the rest of the world.

It should also be pointed out that the fact there is only one fibre fiber optic cable means the only backup is satellite which may not be configured to take the re-0reouted traffic, and in any case may have inadequate capacity.

The ATICS survey of 84 leading tertiary institutions in Africa found 850,000 students and staff with access to a total of only 100Mbps international bandwidth. By contrast, Australia?'s tertiary community of 250,000 share 6Gbps of international bandwidth (although even this is still insufficient to meet their needs).

...